AI coding tools are quietly reshaping software development

They’re making an economic impact, despite not being very good yet

In a viral video posted on X, an 8-year-old girl happily “codes” away. Over the course of 45 minutes, she has Cursor, an AI coding assistant, build a chatbot that replies in the style of Harry Potter. Using only simple text-based prompts, she asks Cursor to create a website, add a textbox with a CloudFlare-powered chatbot, and finally tweak the background style. At each step, Cursor writes code implementing her requests.

“If it does work, it’s going to be so cool!” she says excitedly while waiting for Cursor to change the loading icon to a spinning lightning bolt.

The young coder isn’t the only one drawn to the new tools springing up in the AI scene. Amid worries about AI’s small revenues at the big tech companies, AI coding assistants like Cursor and GitHub Copilot are one area where AI is starting to make an economic impact. Despite their significant current limitations, we already live in the world where the majority of software engineers work alongside AI.

Fewer than 10% of software engineers used AI coding tools in early 2023. But by June 2024, that percentage shot up to 62%, with an additional 14% saying they planned to start soon, according to survey data from 60,000 developers.

This uptick in AI tool use is driving up programmer productivity. A study of large randomized controlled trials of 4,867 software developers at Microsoft, Accenture, and an anonymous Fortune 100 company found a 26% increase in completed tasks among developers using the coding assistant GitHub Copilot. A smaller (199 respondents) survey from consulting firm Bain found that developers’ coding efficiency improved by around 30%, contributing to an overall efficiency improvement of 10% to 15% (because only half of the developers’ time was spent coding). Bain estimated that future benefits could be substantially larger when companies fully integrate AI into their work systems.

While Bain reports that companies are not yet fully monetizing these productivity improvements, companies are already reporting financial gains. Amazon CEO Andrew Jassy claimed last year that the company saved $260 million and 4,500 developer years by using their GenAI coding assistant, Q, to upgrade their framework, calling it a “game changer.”

These tools have had an even larger disruption in startups, where speed is valued over efficiently managing massive codebases. Several entrepreneurs told Transformer they were hiring fewer developers because AI was doing the work — a trend that is proving common. One entrepreneur, Peter Elam, said: “You could probably do with a team with three now, what it would take a team of 10 to do before.”

Charles Dillon built his unannounced startup’s entire prototype from scratch using Cursor, an experience which he likens to his previous role managing a team of developers. The most interesting part: Dillon isn’t actually writing the code. “I've never actually written from scratch any of this programming language,” he said, but the AI has “written for me tens of thousands of lines of code that do exactly what I want to be done.” He explained: “It's really, really good, because it can build the first version of a thing and it’ll do what you wanted, or if the first piece of code it produces doesn’t work, you can usually just tell it the error that's been returned, and it will immediately know how to fix that problem.”

But while AIs can be a boon for junior developers, their benefits are less pronounced for more experienced developers. A large study found that AI increased junior developer productivity by 40% — but it only boosted senior developer productivity by 7%.

Part of this difference comes from the way AI coding assistants work. They quickly produce code, but that code usually contains many errors or may simply not work. The 8-year-old coding a Harry Potter chatbot didn’t need to build anything complicated (like a secure log-in) but even she still needed to ask the AI to fix its code when it failed to implement a simple record of the chat log. Even simple tasks need a human reviewer to prompt the AI to fix its mistakes. In one test, AIs could solve bugs, but were unable to understand what caused the bug and hence kept making mistakes.

More senior developers tend to work on complex problems that AI would struggle with, while junior developers are often assigned routine maintenance, simple improvements, or bug fixes — tasks that AI tools are better at handling. Junior programmers also often code more slowly and create more bugs, so buggy AI code is less of a decrease in quality from their normal output.

Another challenge is that AIs can’t manage large, complex code bases. Context windows — the amount of information relevant to an AI’s current task that it can store and use — are limited in size. This means that even if an AI becomes competent at coding small projects, it would struggle with the large code bases that many companies rely on. According to Dillon, once his code base got beyond a few thousand lines of code, he needed “to be a lot more careful” using the AI tool, or else his codebase “would just break all the time.” Large tech companies might have millions or billions of lines of code, far beyond what an AI coding assistant can manage efficiently. Humans like Dillon still need to oversee the AI, fixing errors and shepherding it along the way, in order to produce usable code.

The AI is like an extremely novice coder — it makes mistakes and doesn’t understand the big picture for what it's creating. But unlike a novice coder, it can write code in seconds, at virtually no cost.

When AI produces code this cheap and fast, fixing the bugs becomes worth it. According to Google CEO Sundar Pichai, “more than a quarter of all new code at Google is generated by AI, then reviewed and accepted by engineers.”

This has led some to anticipate that the role of junior developers will change to one of being a “nanny” for AI coding assistants — or even be replaced entirely. “The end of junior devs as we know it is coming for sure,” Quinn Slack, CEO of Sourcegraph, told another publication last year. “They need to adapt and change. The role of and expectations for a junior dev will look very different in a couple years.”

There are already signs that AIs are starting to displace humans. Anthropic’s president said that Claude is boosting their developers’ productivity, leading the company to rethink hiring plans for this year. On a smaller scale, Nathan Young, who runs a software agency, told Transformer that using AI tools “feels increasingly competitive with hiring additional developers.” On net, however, the total number of software jobs is predicted to grow, as enhanced productivity from humans working alongside AI drives ever more demand for services.

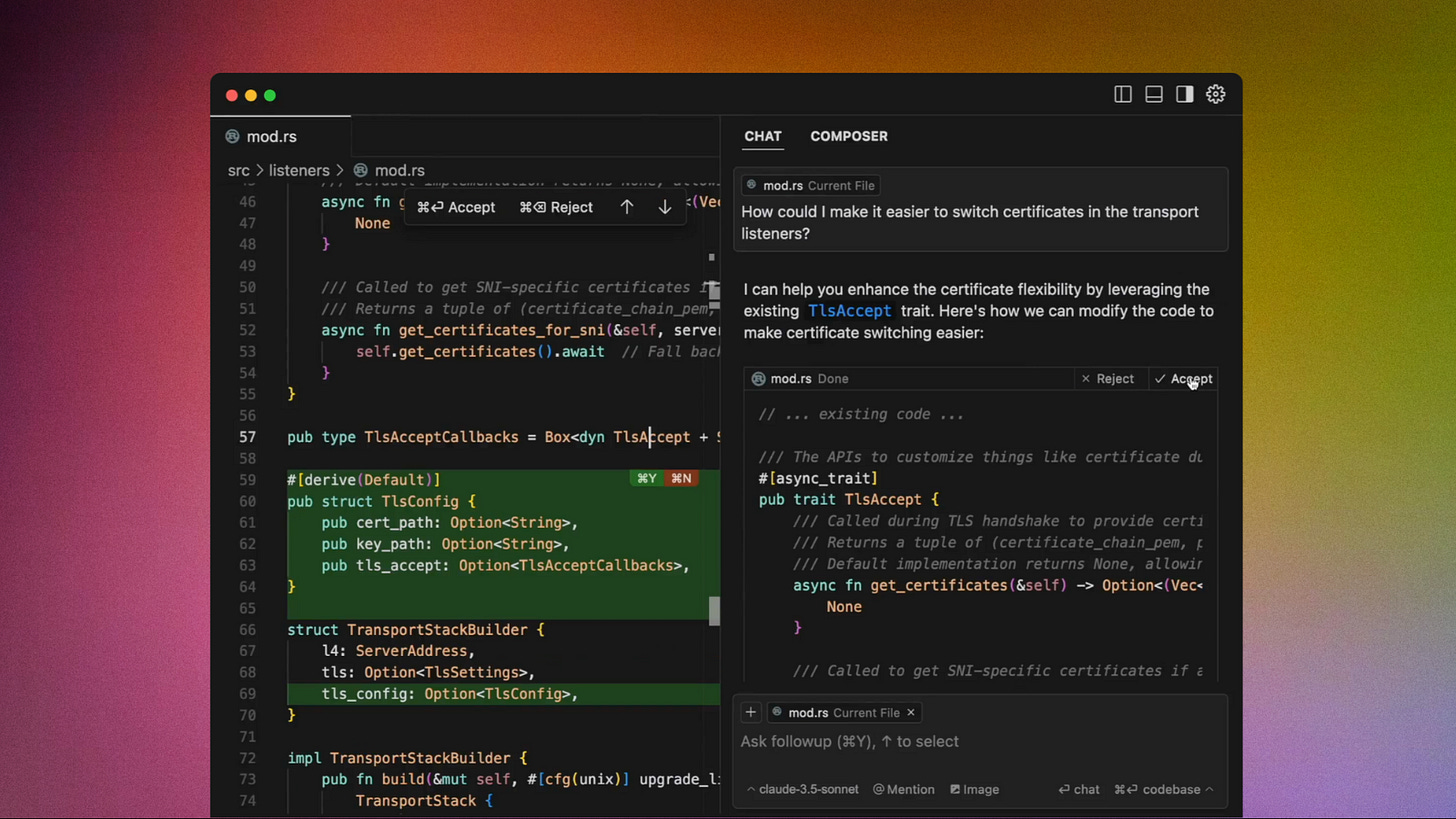

Companies, meanwhile, are working hard to improve their tools. Anthropic just released a GitHub integration so that developers can connect code repositories directly to Claude, and Cursor is currently training a custom model to overview companies’ code bases and efficiently select the most relevant chunks.

The implications of such improvements could be immense. The World Economic Forum anticipates “near-universal uptake” with 99% of information and technology services using AI tools by 2030. Consulting firm Gartner predicts that generative AI will require 80% of software engineers to upskill for working alongside AI by 2027 as we head toward a world where “most code will be AI-generated rather than human-authored.” Sam Altman, meanwhile, has said he’s in a betting pool for “the first year that there is a one-person billion-dollar company”. If the economic impact of current AI coding tools is any indication, that might be a reality sooner than you expect.

Update March 1, 2025: This piece has been updated to clarify Dillon’s workflow.